72.14%

That's a good chunk, right? Say, if I were to eat 72.14% of a Domino's pizza, we'd all be like, “WHOA, ASH IS MURDERING THAT THING.”

Similarly, if you were to drink 72.14% of the wine, I might murder you. This is an equal opportunity kitchen, thank you very much.

Because 72.14% is pretty basically three-fourths of a whole, which is otherwise known as “most of it!” And in the year 2016, most of the people! in the rural town where I grew up in Susquehanna County, Pennsylvania—New Milford, PA—voted for Donald Trump.

72.14%.

To put this in context, New Milford town and borough together add up to 1,235 people, 891 of which voted for Trump, 297 for Clinton, and 47 for the doomed “Others.” So when I say this is a “small, rural town,” I'm not talking about a Desperate Housewives-like suburb with a Bonefish Grill, brick-laden townhomes, and Whole Foods “Towne Centers,” spelled with an “e.”

Instead, there's a Pump ‘N Pantry convenience store. Eight miles up the road, there's a Smokin' Joe's cigarette outlet. There are numerous firework warehouses, bars that have pencil-scrawled names of the people who are banned that month, and an empty parking lot where the old roller skating rink burned down.

Also—most importantly—there is also a large population of people whose needs have been left behind, just like so many other rural communities covering the United States. But politicians don't care about these types of places. In fact, economists have even urged small-town residents to abandon their homes and find opportunity elsewhere.

And that's precisely why, when Donald Trump came along in 2016, he got elected.

Not necessarily out of ignorance—but out of spite. Out of hope. Out of last-ditch attempts and final sets of prayers.

Since the election, however, while Donald Trump was busy horrifying the rest of the world with his behavior, folks in rural areas kept cheering him on—but perhaps for new reasons than when they began.

Before, it was about a promise that he made.

After, it was about a power that they found.

For the first time ever, they became a part of the conversation. They had a side! They WERE a side. They were represented. Now, it wasn’t just a conversation among the Washington elite; it was something in which they were an active participant. It was something they had started.

What they had discovered was agency.

Agency, something that rural towns in decline haven’t had for so, so long. For so, so long they have been dependent upon jobs being brought to them; opportunities finally coming their way. It’s like sitting there with your hands cupped for eternity, waiting for someone to give you a shot. (I talk about this in my book.)

But then Donald Trump shined a spotlight on these kinds of places and said: I’LL help you. I’ll negotiate on your behalf and I’ll make the government work for YOU. Let’s rally together and we’ll do it. (Whether he kept that promise is a different story.)

So rally together, they did.

And rally together again, they will.

Because, hi: folks in rural America are planning on voting for him (again).

Perhaps that explains why the New York Times physically went out to my hometown in Susquehanna County, just a couple of weeks ago, and interviewed my high school classmate's father—and my own father's good friend from our time in Susquehanna County—a man named Rick Ainey.

Rick Ainey is the Democratic Chairman. We were Democratic transplants from Philadelphia. Most urban dwellers are Democrats. But most rural dwellers are not. And Democrats should be very concerned about places like my hometown.

Thus, the name of the article the New York Times published about Rick Ainey & my hometown: Will Trump Win Pennsylvania Again?

Inside, the article talks about the classic formula for a Democrat to win in Pennsylvania: “Come away with huge margins in the state’s two big urban centers to offset deficits in the rural counties, some of them so small that they are sometimes said to have more bears than people.”

That statement alone illustrates how little politicians have cared about areas like these for, well…ever. The grand plan is not to cater to them, but to…offset them. Write them off. Render them…irrelevant.

Is it any wonder?

Even though I’ve been, frankly, shocked to hear that many of my high school classmates were still planning on voting for Trump for a second term—I don’t suppose I should have been. In my mind, I was thinking that the whole “Make America Great Again” promise was already shown as a sham—and they’d see that he was a bullshit artist of the first degree.

But I, along with the rest of the world, underestimated something very important:

Whether Trump has made good on his promise is subjective.

To the rest of us, he has failed miserably, been reckless in his duties, become a dangerous liability, and made us the laughing stock. However, to rural voters who voted for him based on a promise that they really, really wanted him to make good on, he *is* making good on that promise.

Not because of the economy (let’s face it, most folks living in rural America aren’t benefitting from the stock market, and a town in decline is a negative economic asset that no one’s investing in).

And not because they’ve got more access to education, jobs, or wealth than they did four years ago.

And not because manufacturing has actually come back (that’s never going to happen).

But rather, Trump is making good on his promise in their eyes, because he has made their towns relevant again. He has made their struggles seem important—even if he hasn’t *actually* prioritized them.

For them, America is becoming great again, because small towns matter again. (Or at least, via propaganda they do.)

And the fact of the matter is this: a bullshit artist is not a bullshit artist when he’s on your side. He’s your ally. He’s your friend. He’s helping you “beat” the other side—even if it means pulling punches and playing dirty.

When we smell bullshit, they smell leadership.

Donald Trump is exactly who they want him to be: someone who finally stands up to the bullies they face. In their eyes, we are the bullies, not him.

As a result, something bizarre is happening: the more unpresidential he is, the more they desire him as president.

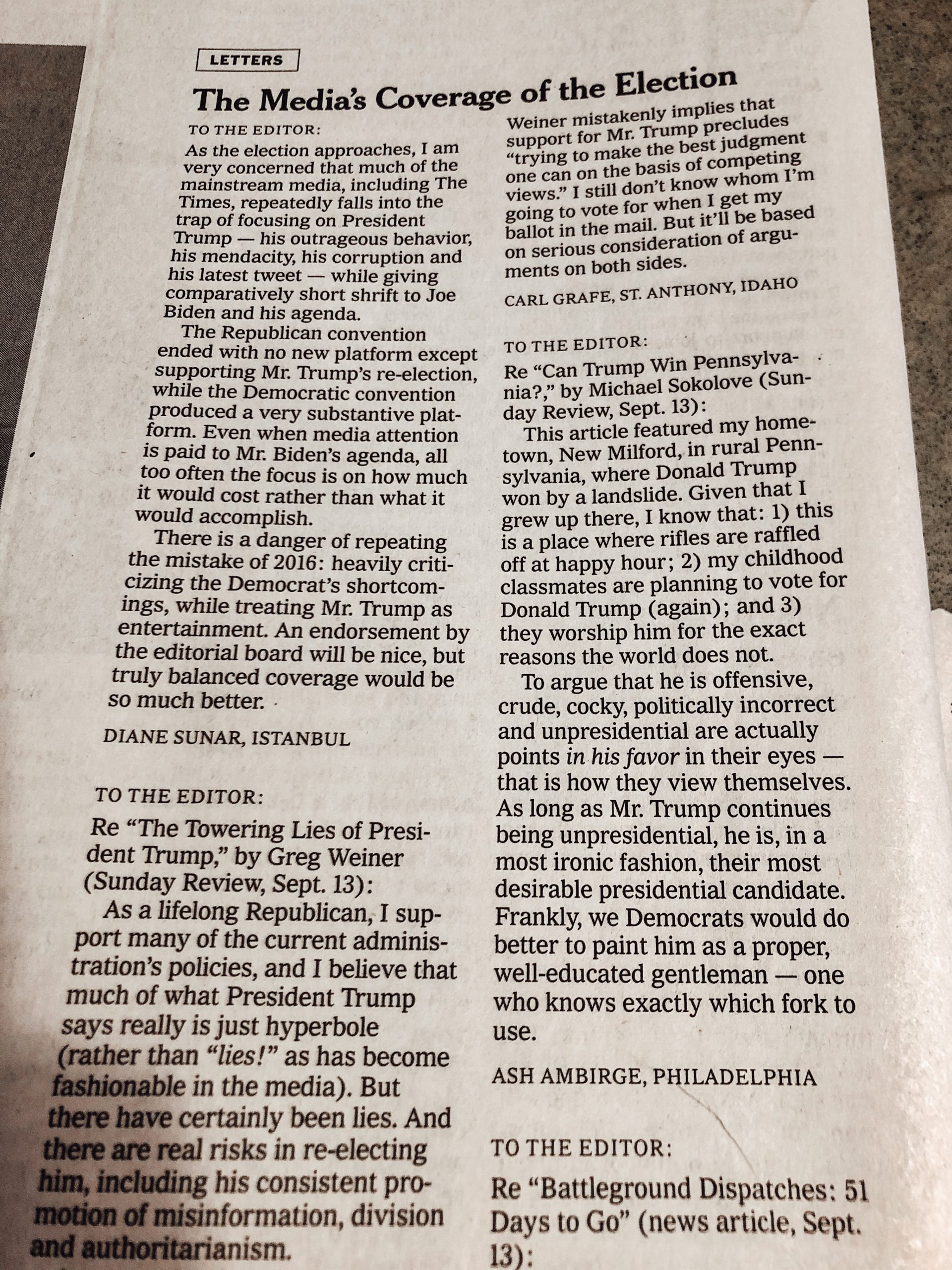

And that’s why I wrote a letter to the editor of the New York Times expressing that sentiment. And I suspect that’s why the New York Times published it this past Thursday, both in print and on the web. (For context: they receive 1,000 letters per day, and can only publish 15 between print and web, so this was an honor.)

Granted, I was a bit cheeky there—you’re limited at 150 words and sarcasm admittedly got the best of me—but my interest, curiosity, and commitment run deep. I’ve been asking a lot of questions lately, one of which is simply this: how can I be a better bridge?

Because no matter what happens in November, one thing is certain: presidents come and go, but the people are here to stay. And we must find a way to empathize with one another and use humanity as a salve, or we risk far graver threats to our society, and soon.

Right now, urban America and rural America are two different countries on two different continents, with distinct cultures, narratives, belief systems, priorities, and ways of looking at the world. Both are looking at the other in complete disbelief, and both are growing in apathy by the day.

And yet, I can’t help but wonder: how much of the disdain for the other side goes back to a fundamental breakdown of simple communication? For example, whoever came up with the term “defund the police” clearly did not work in branding. That’s a terrible label for a well-intentioned idea—and dare I say it, an irresponsible label as well. Of course it’s going to be divisive. Of course you’re going to create a chasm where there didn’t have to be one.

Which makes me think about the value of words, once again.

And it makes me think about my role in all of this. There are very few people whose realities have allowed them insider access to both sides.

I think about my hometown and where I grew up.

I think about my college degree in Communications and Foreign Languages.

I think about my master’s degree in Linguistics.

I think about my adulthood spent traversing cultures and lands.

I think about my career as an advertising writer, where I work to sell ideas.

I think about the blog I wrote that brought people together from around the world.

I think about my voice and its ability to relate & disarm.

I think about the book I published that helped me use my voice to inspire.

I think about my identity as both a global citizen of the world, and the daughter of a small town in rural America.

I think about how I can roll up into any trucker bar in the boonies and pound a Bud with the best of them, right after de-boarding a plane from London where I sipped the most elegant champagne.

And I think about how uniquely qualified I may be to be the bridge.

In the strangest of synchronicities, if I blink too hard it could almost seem like I was made for this moment in time—and you KNOW I don’t say things like that. (Ever.) But in many ways, I can’t help but think that a translator of sorts is required. Just like you’d have a translator or interpreter in between countries who speak two different languages, perhaps we need one in America now, too.

We need to bridge the abyss that could devastate our population for the rest of our lives.

So, I’m on a mission. I’m not entirely sure of its shape, whether it’s facilitating a pen pal program between rural and urban voters; whether it’s an Instagram account humanizing the real lives of rural voters; whether it’s writing a series of love letters myself, to both sides, in earnest; whether it’s using my voice to help break down issues on both sides and explain them in a way that people can actually UNDERSTAND. Or whether it’s just making us all human again, one word at a time.

But I want your help. I want to know what strikes you as useful and interesting—and if you’ve got any contacts at any publications / newspapers / magazines that may want to publish a column to this effect, I’d sure appreciate a conversation.

There are many things we can spend our time on each day. But once in a while, something comes along that you must spend your time on.

That’s what’s called a passion.

And following a passion is sometimes the most generous act of all—because it is hard. And it is complex. And it is big.

But it is always worth it.